Not every product runs on the latest stack — and that’s not always a bad thing. Many teams are supporting real customers, real revenue, and real operations on systems that were built years ago. The tech might be dated, but the business is still working.

So why consider selling?

Because maintaining a legacy system comes with trade-offs: slower development, rising support costs, limited hiring options, and growing pressure to modernize. And at some point, it may make more sense to hand it off than to rebuild it yourself.

Here are a few common scenarios:

- You’ve outgrown it. The system got you this far, but scaling it further would require more time, money, or risk than you’re willing to take on.

- It still delivers value. The architecture might be old, but the users, contracts, or workflows it supports are still meaningful — and worth something to the right buyer.

- You inherited technical debt. Maybe you weren’t the one who built it. Maybe your team did what they could with the tools they had. Either way, the current state isn’t where you want to keep investing.

- There’s a window to exit. Market conditions, acquisition interest, or internal strategy might point to a sale — and cleaning up the tech story is part of making that possible.

- You want to reduce risk. Aging components, gaps in documentation, and one or two people with all the context — it’s manageable now, but fragile long-term.

If any of that sounds familiar, this guide is for you. We’ll walk through how to document what you’ve got, identify the real risks, and build a simple, credible plan that helps buyers understand the system — and see the value behind it.

Define the Legacy Scope

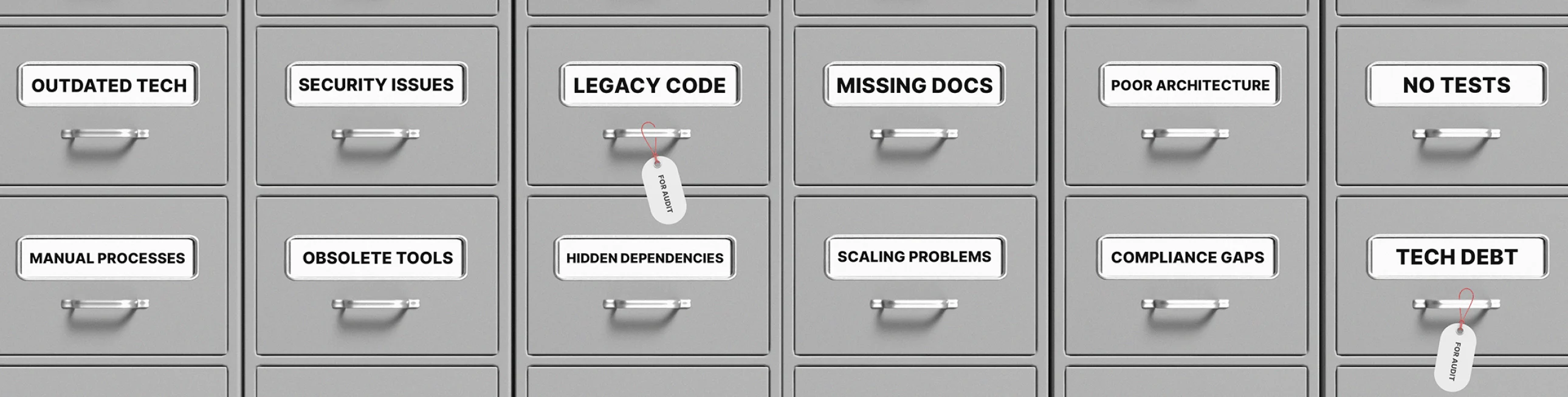

Before you can clean anything up, you need to be clear on what you’re actually working with. “Legacy” doesn’t just mean old — it means hard to change, hard to scale, or hard to transfer.

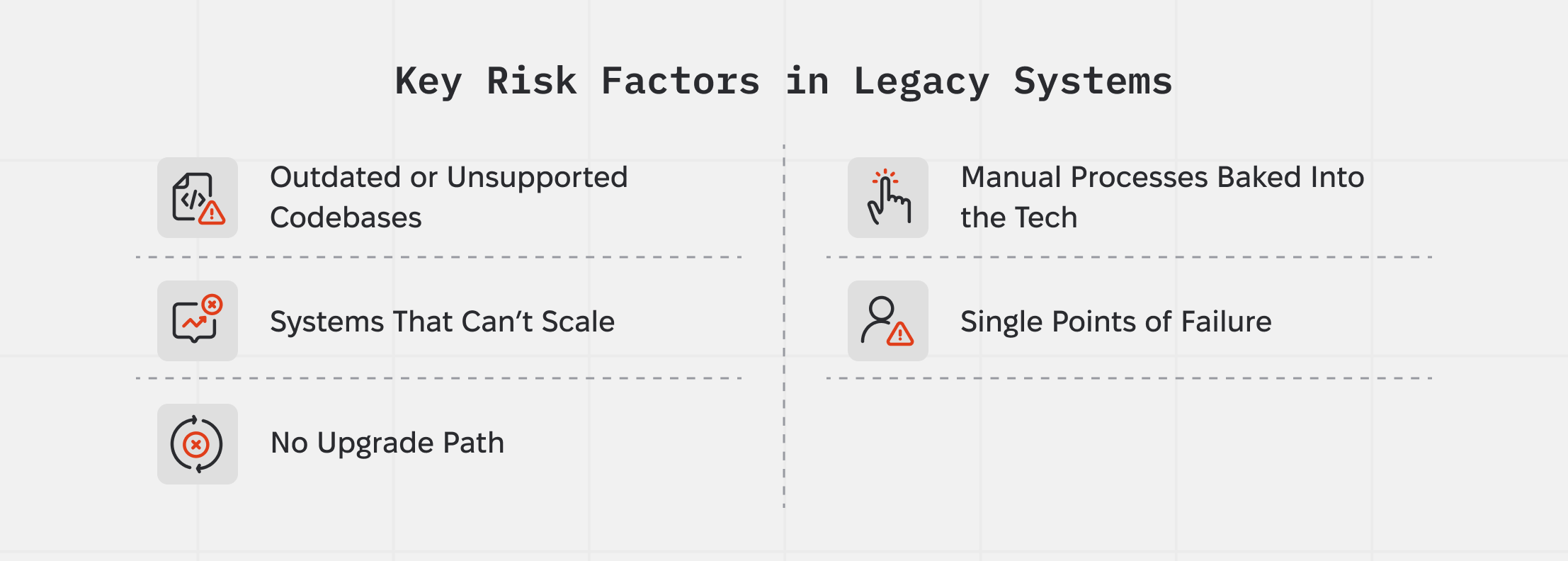

Here’s what typically qualifies:

- Codebases that are outdated or unsupported. Think VB6, COBOL, Flash, AngularJS, jQuery-heavy apps, or tightly coupled monoliths with no tests.

- Systems that can’t scale easily. Apps with fixed capacity, rigid infrastructure, or no support for modern deployment (e.g. containerization or cloud environments).

- Tools or platforms with no upgrade path. If the vendor’s ended support or you’re locked into a customized solution that can’t be replaced without rewriting, buyers will flag it.

- Manual processes baked into the tech. Anything that depends on human intervention to “make it work” will raise concerns — especially in ops, billing, or compliance flows.

- Single points of failure. Legacy often means only one or two engineers still understand how it works — and they’re busy (or leaving).

Patterns Buyers Flag Fast

Here’s what happens in practice. A buyer sits down with your tech team and asks for documentation. The architecture diagram is missing, or five years out of date. The data model isn’t written down — it lives in one senior developer’s head. They request a test suite; you point to a few scripts and manual QA notes. Deployment? It’s handled manually by one DevOps engineer who SSHs into a box and uploads new code. The database? It’s still accessed directly from the frontend, with no API layer.

None of these are dealbreakers by themselves. But together, they send a message: this system is going to take time, people, and money to stabilize. That’s the risk buyers are calculating — and the narrative you need to get ahead of.

Prepare Your Aging Stack for Buyer Review

Legacy products don’t derail deals because they’re old. They do when risks are unclear or undocumented. Before buyer review, identify the key risks and document the system to show control.

Build a Remediation Plan

Once you’ve mapped the issues in your system, the next step is to decide what to fix, what to leave as-is, and what to disclose with context. Buyers expect clarity and a realistic plan.

Case Examples: Modernizing Legacy Systems Before Exit

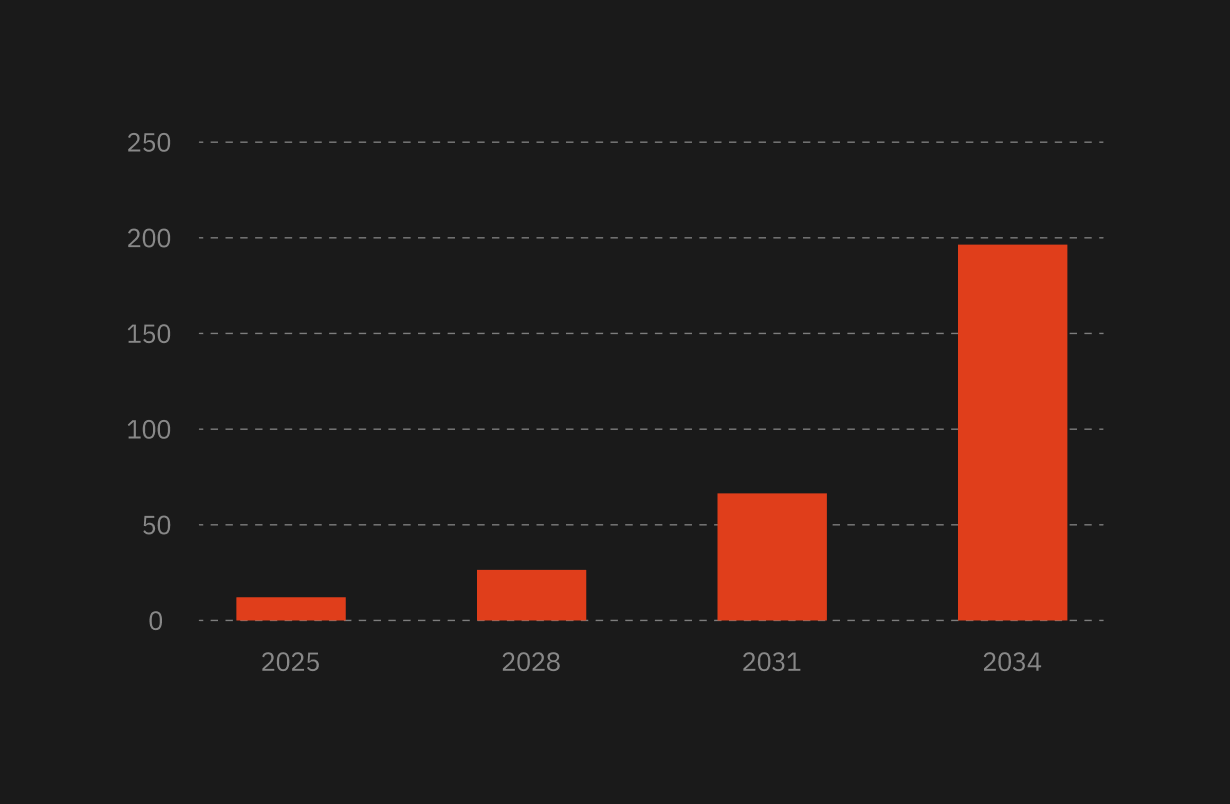

Modernization isn’t just about cleaning up tech—it’s about making the business easier to buy, scale, and believe in. Two standout cases prove the point.

Quicken was known for its desktop-based personal finance software—stable but outdated. After being carved out from Intuit, the product was functional but tied to legacy code and local installs. H.I.G. Capital, the private equity owner, made modernization a priority. The team migrated key functionality to the cloud, cleaned up technical debt, and launched a mobile-first product, Simplifi, built for subscription growth. These changes weren’t just technical—they were strategic. In five years, Quicken doubled its active users, grew revenue by 50%, and lifted customer satisfaction by 25 NPS points. When Aquiline Capital acquired Quicken in 2021, it wasn’t buying an old brand—it was buying a modern SaaS asset with a clear trajectory.

Talend, a data integration platform, had similar legacy exposure. Its early architecture was built for on-premise environments, which no longer aligned with market demand. The company made an aggressive shift to cloud-native infrastructure, refactoring critical systems and expanding platform capability. Despite pandemic headwinds, Talend delivered on its roadmap and positioned itself as a cloud-first market leader. That clarity and execution mattered: Thoma Bravo acquired Talend for $2.4 billion—a 29% premium over its market price. The board called out the modernization strategy as central to the deal.

In both cases, technical cleanup wasn’t optional—it was the lever that de-risked the acquisition, accelerated the deal, and improved valuation.

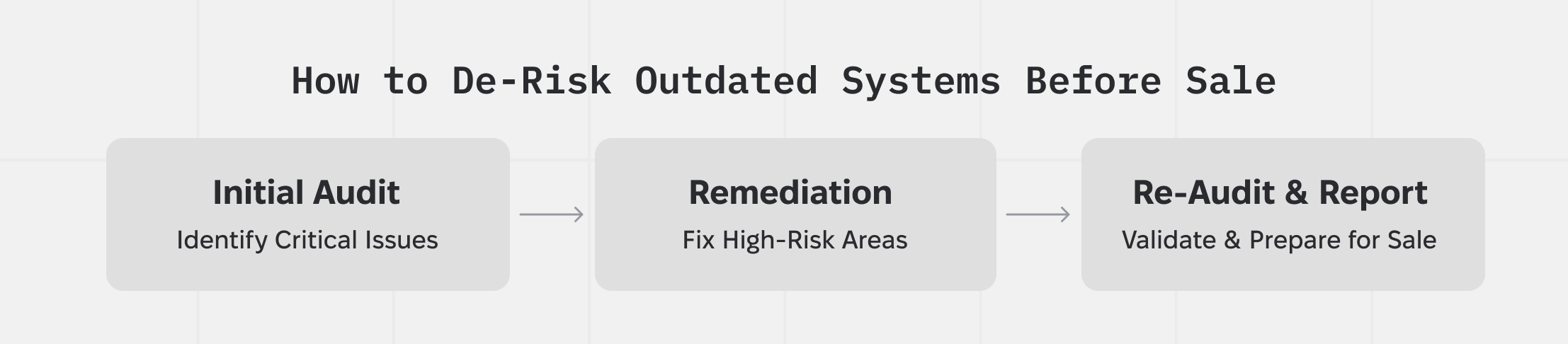

Conclusion: Audit First, Then Fix What Matters

Before selling an outdated system, a structured tech audit is essential. It surfaces real risks—untested code, unsupported legacy modules, security gaps, missing documentation, and overreliance on a few individuals.

The process is simple:

- Initial audit – Identify critical weaknesses across architecture, codebase, security, and operations.

- Remediation – Prioritize and address the high-risk issues. This can take weeks or months, depending on system complexity.

- Re-audit – Confirm fixes and compile a clear technical report to support buyer due diligence.

This approach doesn’t require a full rebuild—just clarity and control. When the risks are known, documented, and partially mitigated, buyers are more confident—and deals close faster.

.png)

.webp)