Selecting a Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) engine often becomes a significant decision only after a platform encounters terminology growth, expanding profiles, heavier workflows, or rising ingestion volumes. By then, teams are dealing with slow iteration, unexpected constraints, or extra components added to compensate for engine behavior.

This article addresses that gap. Many decision-makers sense the pressure points but lack a structured way to connect them to the capabilities of the FHIR layer. To support that evaluation, the article introduces a framework built around five dimensions that consistently influence system behavior: terminology, validation, search execution, extensibility, and operational ownership.

Using this framework, we examine how different engines handle these demands, including a comparison of Azure’s managed FHIR service and the HAPI FHIR Server. The aim is to give readers a model they can apply to their own platforms and understand which conditions point toward one engine or another.

FHIR Infrastructure As a Strategic Decision

The choice of FHIR engine influences several long-horizon commitments inside a healthcare platform. Once the system begins supporting treatment programs, pharmacy or payer workflows, and regulatory reporting, the FHIR layer becomes part of the governance model as much as the technical design.

Profile updates, terminology growth, new program requirements, changes in ingestion volume, and adjustments to integration rules all pass through this layer. The engine determines how quickly these shifts can be absorbed, how much work settles on surrounding components, and how predictable the system remains as the product portfolio expands.

For teams operating in multi-program or multi-tenant environments, this shapes planning cycles, partner onboarding timelines, regulatory preparation, and the ongoing cost of maintaining the ecosystem. These are long-term effects that extend beyond implementation work, which places the selection of a FHIR engine in the same category as decisions around data platforms, workflow engines, and identity systems.

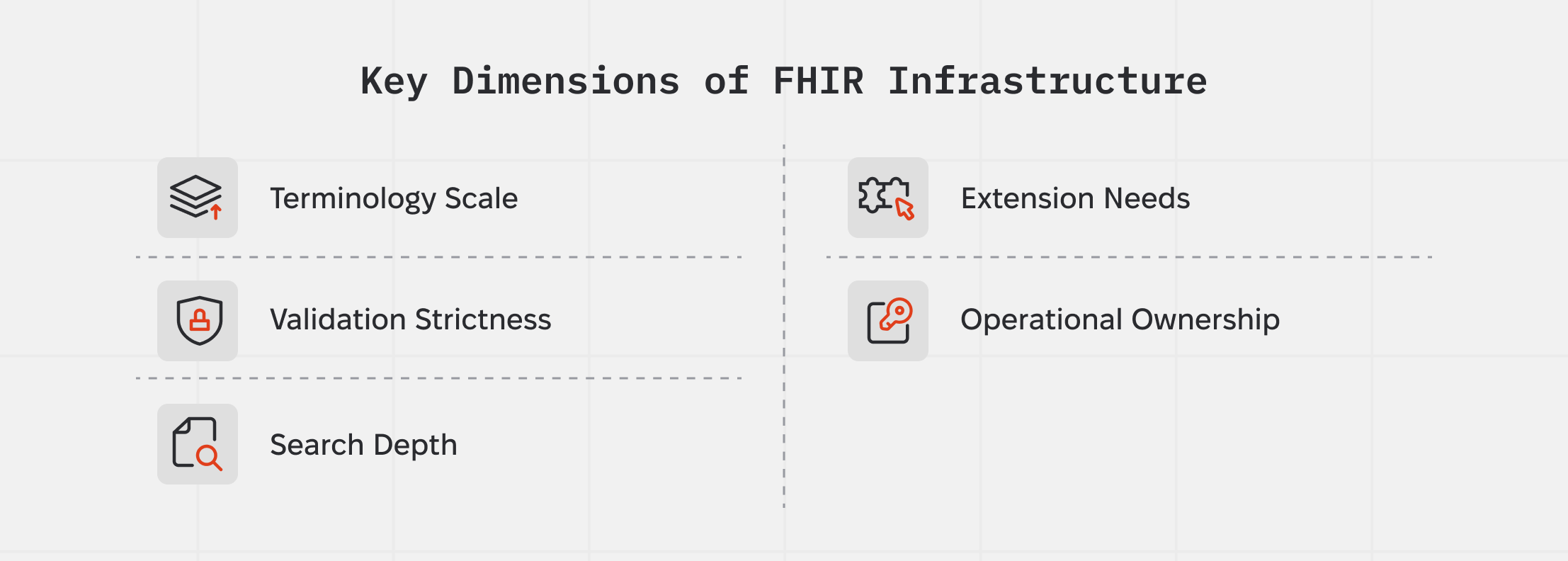

Five Dimensions That Define FHIR Engine Fit

Healthcare platforms place uneven pressure on the data layer as they scale. Terminology sets expand, profiles accumulate nested constraints, workflows rely on deeper query chains, and ingestion pipelines begin to push millions of writes during nightly windows. These patterns expose how the engine behaves under stress. Five dimensions consistently reveal that behavior and can be used to evaluate fit.

Terminology scale

Large ValueSets (drug catalogs reaching 30–70k entries, payer-plan structures with seasonal updates, PBM directories with overlapping identifiers) require $expand, filtering, paging, and text search at near-interactive speed. Engines without internal terminology support shift this work to external indexes, which increases latency and raises maintenance overhead.

Validation strictness

Profiles with nested extensions, multi-level invariants, conditional elements, and fixed terminology bindings demand predictable enforcement during writes. If an engine doesn’t resolve profile dependencies or reference integrity internally, downstream systems absorb inconsistent data—typically through reprocessing or compensating ETL steps.

Search depth

Workflows involving chains like MedicationDispense?medicationrequest.encounter.patient={id} or include/revinclude across multiple resource layers depend on flexible indexing and stable query resolution. Engines with fixed indexing models often exhibit latency spikes when datasets cross certain thresholds or when filters touch clinical and administrative fields simultaneously.

Extension needs

Identity tokenization, rule-driven transformations, program-level logic, and derived resources often require interceptors, request pre-processing, or custom operations. Without server-side extension points, these processes move to upstream services, creating duplicated logic and additional network calls.

Operational ownership

Ingestion-heavy platforms rely on tuning controls for thread pools, indexing order, concurrency, caching layers, and batch commit behavior. Compliance programs require detailed audit logging, predictable upgrade windows, network isolation, and stable versioning. Engines differ sharply in how much operational surface they expose.

These five dimensions form a practical assessment framework: they identify where the engine absorbs complexity and where surrounding systems must compensate. The same dimensions also allow teams to forecast long-term fit as terminology expands, programs multiply, and workflows deepen.

How Engine Differences Surface Under Load: A Dimension-by-Dimension View

As terminology sets grow, profiles get deeper, workflows get longer, and ingestion volumes climb, the differences between engines stop being theoretical. Pressure shows up in uneven places: terminology expansion, validation on write, query depth, and day-to-day operability.

Below is a practical view of what tends to strain first, what teams usually notice, and how the same “FHIR capabilities” get implemented in Azure (managed) vs HAPI FHIR (self-hosted).

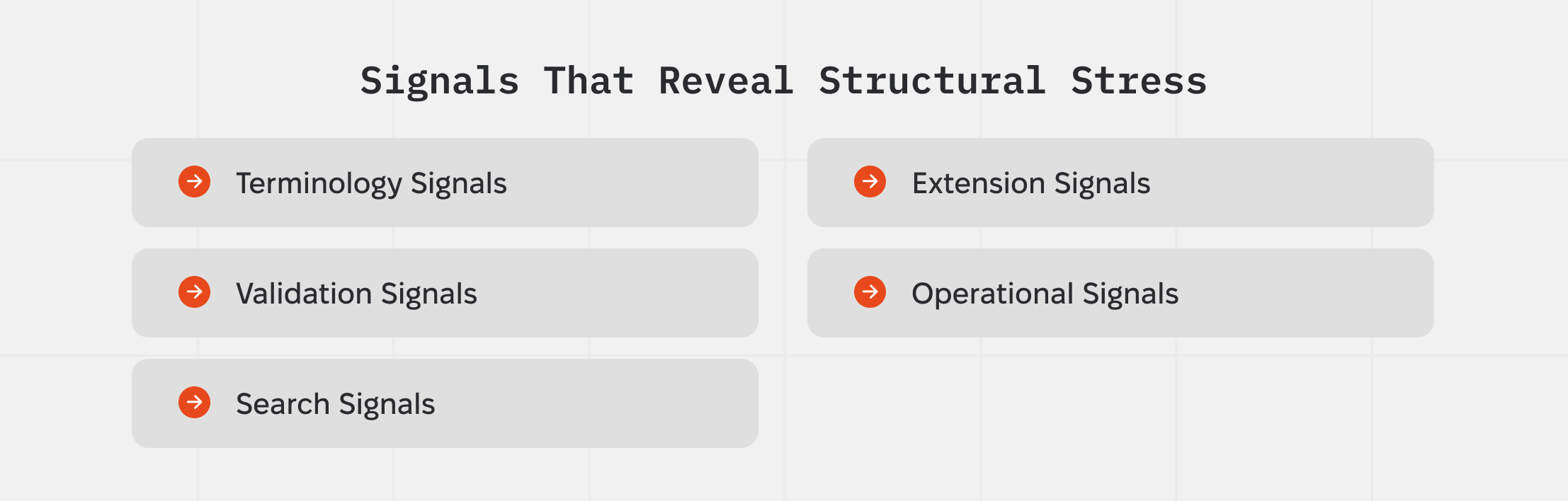

How to Evaluate Your Platform — and What Our Own Signals Looked Like

Platforms accumulate pressure unevenly. Terminology grows faster than expected, workflows deepen, ingestion volumes rise, and new clinical or payer programs introduce additional structure. The framework from the previous section works as a diagnostic tool: instead of guessing where a FHIR engine may struggle, teams can watch for specific signals that reveal structural stress.

Below are the kinds of signals that matter — followed by how similar signals shaped our own engine decision.

Terminology Signals

When drug catalogs expand, payer-plan files multiply, or PBM lists introduce overlapping identifiers, lookup endpoints become increasingly active.

Signals to track:

- repeated full ValueSet loads

- UI components relying on client-side caches

- lookups slowing as dictionaries grow

We saw early versions of this pattern. Terminology calls became one of the busiest categories, and the system needed server-side filtering, paging, and text matching — not external indexing layers.

Validation Signals

As platforms introduce new programs, profiles accumulate deeper constraints and more nested extensions.

Signals to track:

- downstream workflows correcting malformed resources

- references misaligned with program logic

- profile changes causing inconsistent data across services

Our pipelines began surfacing mismatches between stored resources and workflow rules. This pushed the team toward predictable write-time validation instead of patching issues after ingestion.

Search Signals

Workflows often grow from simple lookups into multi-hop chains connecting patients, programs, prescribers, and medication records.

Signals to track:

- multi-call API assembly

- unpredictable query times

- caching layers expanding to compensate for search depth

We reached a point where chained queries and include/revinclude patterns became core to program logic. That required stable indexing and flexible search features inside the engine.

Extension Signals

Identity matching, rule-based transformations, and derived records naturally shift closer to the data layer over time.

Signals to track:

- domain rules implemented in several upstream services

- repeated logic appearing in ETL, workflow engines, and APIs

- difficulty keeping derived-resource logic consistent

During development, identity resolution and program-specific transitions clustered around the data. The team needed server-level hooks so these steps ran once, in the correct place, instead of in multiple pipelines.

Operational Signals

Platforms with large ingestion windows, multi-tenant traffic, or strict audit requirements rely on controlled tuning and flexible deployment.

Signals to track:

- ingestion times that vary across releases

- unclear indexing behavior

- difficulty placing the engine inside private or hybrid networks

Our deployments spanned Azure, AWS, and internal subnets with different compliance requirements. Predictable tuning, version stability, and network placement became essential.

How These Signals Guided Us

When we mapped our own signals to the framework, a pattern formed:

- terminology needed to run inside the server

- validation had to be consistent and automatic

- search had to support deep chains without multi-step compensation

- domain logic needed a home near the data

- deployment required full control across mixed cloud environments

That combination shaped the direction of the engine selection. It wasn’t a vendor comparison exercise — it was matching architectural needs to engine behavior.

7. Decision Checklist: Choosing a FHIR Engine for Your Product

Use this checklist during vendor evaluation, architectural planning, or early prototyping. It helps teams identify where their system will place pressure on a FHIR engine — and which capabilities must be guaranteed from day one.

Conclusion

The evaluation work showed where each engine stayed predictable under terminology growth, profile evolution, deeper workflows, and heavier ingestion cycles. By mapping those pressures to the five dimensions, the differences between engine designs became visible enough to guide a long-term architectural choice.

Instead of reacting to issues after they surfaced in production, the teams used these signals to understand what the platform would demand over the coming years. That removed the need for assumptions and clarified which model could support the workflows, data patterns, and operational boundaries already shaping the product roadmap.

With that assessment complete, the selection of a FHIR engine became a resolved question in the architecture — a stable commitment the rest of the system could build on.

.png)

.png)